|

"India is the world's most ancient civilization. Nowhere

on earth can you find such a rich and multi-layered tradition that has remained

unbroken and largely unchanged for at least five thousand years. Bowing low

before the onslaught of armies, and elements, India has survived every invasion,

every natural disaster, every mortal disease and epidemic, the double helix of

her genetic code transmitting its unmistakable imprint down five millennia to no

less than a billion modern bearers. Indians have demonstrated greater cultural

stamina than any other people on earth. The essential basis of Indian

culture is Religion in the widest and most general sense of the world. An

intuitive conviction that the Divine is immanent in everything permeated every

phase of life" says Stanley Wolpert.

Indic civilization has enriched every art and science

known to man. Thanks to India, we reckon from zero to ten with misnamed

"Arabic" numerals (Hindsaa - in Arabic means from India), and use a decimal system without which our modern

computer age would hardly have been possible.

Science and philosophy were

both highly developed disciplines in ancient India. However, because Indian

philosophic thought was considerably more mature and found particular favor

amongst intellectuals, the traditions persists that any early scientific

contribution came solely from the West, Greece in particular. Because of this erroneous belief, which is perpetuated by a wide variety of

scholars, it is necessary to briefly examine the history of Indian scientific

thought. Jawaharlal

Nehru wrote in his book The Discovery of

India: "Till recently many

European thinkers imagined that everything that was worthwhile had its origins

in

Greece

or

Rome

."

From the very earliest times, India had made its contribution to

the texture of Western thought and living. Michael Edwardes author of British

India, writes that throughout the literatures of Europe, tales of Indian origin

can be discovered. European mathematics -

and, through them, the full range of European technical achievement – could

hardly have existed without Indian numerals. But until the beginning of European

colonization in Asia, India’s contribution was usually filtered through other

cultures.

"Many of the advances in the sciences that we

consider today to have been made in Europe were in fact made in India centuries

ago." - Grant Duff British Historian of India. Dr. Vincent Smith has

remarked, "India suffers today, in the estimation of the world, more

through the world's ignorance of the achievements of the heroes of Indian

history than through the absence or insignificance of such achievement."

Medical Science

Astronomy

Earthquakes

and Meteorology

Fables, Music and Games

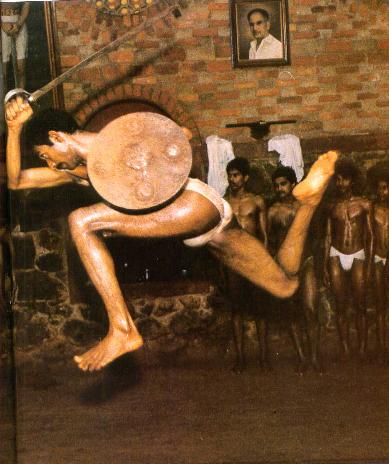

Martial

Arts

Philosophy

Government

and Constitution

Law

Democracy

Logic

in Ancient India

Religion

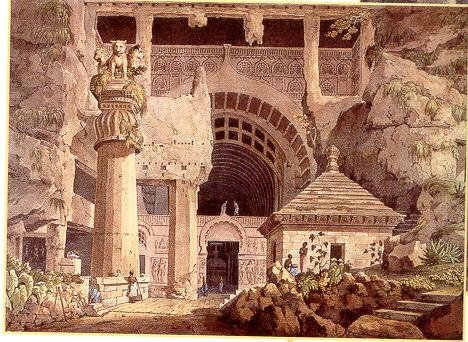

Art and Architecture

Art

of Writing in Ancient India

Literature

Agriculture

Textiles

Medical Science

The science of medicine, like other

sciences, was carried to a very high degree of perfection by the

ancient Hindus. Their great power of observation, generalization and

analysis, combined with patient labor in a country of boundless

resources, whose fertility for herbs and plants is most remarkable,

place them in an exceptionally favorable position to prosecute their

study of this great science.

Lord

Ampthill, British Governor, (February 1905) said at

Madras: "Now we are beginning to find out that the Hindu

Sashtras also contain a Sanitary Code no less correct in principle,

and that the great law-giver, Manu, was one of the greatest sanitary

reformers the world has ever seen!"

Sir William Jones

(1746-1794) came to India as a judge of the Supreme Court at Calcutta.

He said with prophetic warning " Infinite advantage may

be derived by Europeans from the various medical books in Sanskrit,

which contain the names and descriptions of Indian plants and

minerals, with their uses, discovered by experience, in curing

disorders."

(source: Eminent

Orientalists: Indian European American - Asian Educational

Services. p.21).

Horace Hyman

Wilson (1786-1860) says: "The Ancients attained a thoroughly a

proficiency in medicine and surgery as any people whose acquaintance

are recorded. This might be expected, because their patient

attention and natural shrewdness would render them excellent

observers, whilst the extent and fertility of their native country

would furnish them with many valuable drugs and medicaments. Their

diagnosis is said, in consequence, to define and distinguish

symptoms with accuracy, and their Materia Medica is most

voluminous."

(source: Wilson's

Works, Volume III, p. 269.)

Albrecht

Weber

(1825-1901) writes: "The number of medicinal works and authors is

extraordinarily large."

(source: Indian

Literature -

Albrecht Weber

p. 269).

Medicine appears to have been the

oldest Indian science, its roots going back to Yoga practices, which

stress a holistic approach to health, based primarily on proper diet

and exercise. Ancient Indian texts on physiology, identified three

body "humours" wind, gall, and mucus - with which are

associated the sattva, (true or good), rajas (strong), and tamas,

(dark or evil) "strands" of behavior, as primary causal

factors in determining good or ill health. Ayurveda focused on

longevity, honey and garlic were often prescribed. A wide variety of

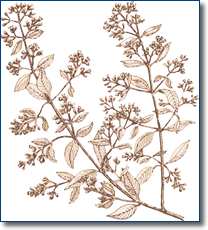

herbs were listed in ancient India's pharmacopoeia. Some of these

medicinal herbs or plant oil have been indeed proved to be cures for

specific diseases. Oil from the bark of chaulmugra trees remains the

most effective treatment for leprosy. India's oldest medical texts

were far superior to most subsequent works in the field.

Anatomy and physiology, like some aspects of chemistry,

were by-products of medicine. As far back as the sixth century B.C. Indian

physicians described ligaments, sutures, lymphatics, nerve plexus, facia, adipoe

and vascular tissues, mucous and synovial membrances, and many more muscles than

any modern cadaver is able to show. They understood remarkably well the process

of digestion - the different functions of the gastric juices, the conversion of

chyme, into chyle, and of this into blood. Anatomy and physiology, like some aspects of chemistry,

were by-products of medicine. As far back as the sixth century B.C. Indian

physicians described ligaments, sutures, lymphatics, nerve plexus, facia, adipoe

and vascular tissues, mucous and synovial membrances, and many more muscles than

any modern cadaver is able to show. They understood remarkably well the process

of digestion - the different functions of the gastric juices, the conversion of

chyme, into chyle, and of this into blood.

Anticipating Weismann by 2400 years

Atreya (ca 500 B.C.) held that the parental seed is

independent of the parent's body, and contains in itself, in miniature, the

whole parental organism. Examination for virility was recomended as a

prerequisite for marriage in men; and the Code of Manu warned against marrying

mates affected with tuberculosis, epilepsy, leprosy, chronic dysepsia, piles, or

loquacity. Birth control in the latest theological fashion was suggested by the

Indian medical schools of 500 B.C. in the theory that during the twelve days of

the menstrual cycle impregnation is impossible. Foetal development was described

with considerable accuracy; it was noted that the sex of the foetus remains for

a time undetermined, and it was claimed that in some cases the sex of the embryo

could be influenced by food or drugs.

The records of Indian medicine begin with the

Arthava-veda;

here embedded in incantation, is a list of diseases with their symptoms.

Appended to the Atharva-veda is the Ayur-Veda

("The Science of Longevity"). In this oldest system of Indian medicine

illness is attributed to disorder in one of the four humors (air, water phlegm

and blood), and treatment is recommended with herbs. Many of its diagnoses and

cures are still used in India, with a success that is sometimes the envy of

Western physicians. The Rig-Veda names over a thousand such herbs, and advocates

water as the best cure for most diseases. Even in Vedic times, physicians and

surgeons lived in houses surrounded by gardens in which they cultivated

medicinal plants.

The great name in Indian medicine are those of Sushruta

in the fifth century B.C. and Charaka

in the second century A.D. Sushrata professor of medicine at the University of

Benares, wrote down in Sanskrit a system of diagnosis and therapy whose elements

had descended to him from his teacher Dhanwantari.

His book dealt at length with surgery,

obstetrics, diet, bathing, drugs, infant feeding and hygiene, and medical

education. Charaka composed a

Samhita

(or encyclopedia) of medicine,

which is still used in India, and gave to his followers an almost Hippocratic

conception of their calling:

"Not for self,

not for the fulfilment of any earthly desire of gain, but solely for the good of

suffering humanity should you treat your patients, and so excel all." Only less illustrious than these are

Vaghata

(625 A.D.), who prepared a medical compendium in prose and verse, and Bhava

Misra (1550

A.D), whose voluminous work on

anatomy, physiology and medicine mentioned, a hundred years before Harvey, the

circulation of blood, and prescribed mercury for that novel disease, syphilis,

which had recently been brought in by the Portuguese as part of Europe's

heritage to India."

Medical

Instruments of the Hindu Scriptures - Susruta (1000 B.C.E) enumerates 125 sharp

and blunt instruments

Surgical instruments - Courtesy: Institute of History and Medicine - Hydrebad,

India.

Refer

to Indian

Institute of Scientific Heritage

***

Sushruta described many surgical operations - cataract,

hernia, lithoromy, Caesarian section, etc - and 121 surgical instruments,

including lancets, sounds forceps, catheters, and rectal and vaginal speculums.

Despite Brahmanical prohibitions he advocated the dissection of dead bodies as

indispensable in the training of surgeons. He was the first to graft upon a torn

ear portions of skin taken from another part of the body; and from him and his

Indian successors rhinoplasty- the surgical reconstruction of the nose-descended

into modern medicine. "The ancient

Hindus," says F. H.

Garrison, "performed almost every major operation except

ligation of the arteries." Limbs were amputated, abdominal sections were

performed, fractures were set, hemorrhoids and fistulas were removed.

(source: History

of Medicine - By F. H. Garrison

Philadelphia., 1929 and The Story of civilizations:

Our Oriental Heritage - By

Will Durant ISBN:

1567310125 1937

p.531).

Mrs. Charlotte Manning

says: "The

surgical instruments of the Hindus were sufficiently sharp, indeed, as

to be capable of dividing a hair longitudinally."

"Greek physicians have done much to preserve and diffuse the

medicinal science of India. We find, for instance, that the Greek

physician, Actuarius, celebrates the Hindu medicine, called triphala.

He mentions the peculiar products of India, of which it is composed,

by their Sanskrit name, Myrobalans."

(source: Ancient

and Medieval India

Volume II. p. 346).

Refer to

Sciences of the Ancient Hindus:

Unlocking Nature in the Pursuit of Salvation – By Alok

Kumar

Sushruta laid down elaborate rules for preparing an

operation, and his suggestion that the wound be sterilized by fumigation is one

of the earliest known efforts at antiseptic surgery. Both Sushruta and Charaka

mention the use of medicinal liquors to produce insensibility to pain. In 927

A.D. two surgeons trepanned the skull of a king, and made him insensitive to the

operation by administering a drug called Samohini.

For the detection of the 1120 diseases he enumerated, Sushruta recommended

diagnosis by inspection, palpation, and ausculatation. Taking of the pulse was

described in a treatise dating 1300 A.D. Urinalysis was a favorite method of

diagnosis.

In the time of

Yuan Chwang

Indian medical treatment

began with a seven-day fast; in this interval the patient often recovered; if

the illness continued drugs were at last employed. Even then drugs were used

very sparingly; reliance was placed largely upon diet, baths, inhalations,

urethral, and vaginal injections. Indian physicians were especially skilled in

concocting antidotes for poison.

William Ward

(1769-1823) notes:

"Inoculation for the

small pox seems to have been known among the Hindoos from time immemorial."

The method of introducing the virus is

made by incision just above the wrist, in the right arm of the male, and the

left of the female. At the time of inoculation, and during the progress of the

disease, the parents daily employ a brahmin to worship Sheetula, the goddess who

presides over the disease."

(source: A

View of the History, Literature, and Mythology of the Hindoos -

By William Ward volume I I p 339 London

1822).

Vaccination, unknown to Europe before the eighteenth century, was known in India

as early as 550 A.D. if we may judge from a text attributed to Dhanwantari,

one of the earliest Hindu physicians.

"Take

the fluid of the pock on the udder of the cow...upon the point of a lancer, and

lance with it the arms between the shoulders and elbows until the blood appears;

then, mixing the fluid with the blood, the fever of the small-pox will be

produced."

Modern European physicians believe that caste

separateness was prescribed because of the Brahmin belief in invisible agents

transmitting disease; many of the laws of sanitation enjoined by Sushruta and

"Manu" seem to take for granted what we moderns, who love new words

for old things, call the germ theory of disease. Hypnotism as therapy seems to

have originated among Indians, who often took their sick to the temples to be

cured by hypnotic suggestion. The Englishmen who introduced hypnotherapy into

England-Braid Esdaile and Elliotson- "undoubtedly got their ideas, and some

of their experience, from contact with India."

(source: The Story of civilizations:

Our Oriental Heritage - By

Will Durant 1937

p.531)

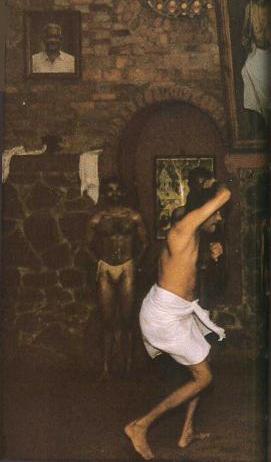

Susruta calls surgery,

"the first and best of medical sciences."

He insisted that those who intend to practice it must have actual experimental

knowledge of the subject. He says: "No accurate account of any part of the

body, including even its skin, can be rendered without a knowledge of anatomy,

hence anyone who wishes to acquire a thorough knowledge of anatomy must prepare

a dead body, and carefully examine all its parts." For preliminary

training, students were taught how to handle their instruments by operating on

pumpkins or cucumbers, and they were made to practice on pieces of cloth or skin

in order to learn how to sew up wounds. Major operations, as described by

Susruta, included amputations, grafting, setting of fractures, removal of a

foetus and operation on the bladder for removal of gallstones. The operating

room, he declares should be disinfected with cleansing vapors. He describes 127

different instruments used for such purposes as cutting, inoculations,

puncturing, probing and sounding. Cutting

instruments, Susruta maintains, should be of "bright handsome polished

metal, and sharp enough to divide a hair lengthwise."

(source: The

Pageant of India's History - By Gertrude Emerson Sen p. 66 - 68).

"The specific

diseases whose names occur in Panini's grammar indicates that

medical studies had made great progress before his time (350 B.C.).

The chapter on the human body in the earliest Sanskrit dictionary,

the Amara-kosha presupposes a systematic cultivation of the science.

The works of the great traditional Indian physicians, Charaka, and Susruta,

were translated into Arabic not later than the 8th century. The

chief seat of the science was at Benares. The name of Charaka

repeatedly

occurs in the Latin translations of Avicenna (Ibn Sina), Rhazes (Al

Rasi), and Serapion (Ibn Serabi).

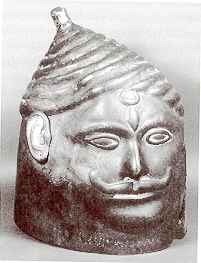

Charaka

(image source: Vishwa

Hindu Parishad of America. Inc - 2002 calendar).

***

Indian medicine dealt

with the whole area of the science. It described the structure of

the body, its organs, ligaments, muscles, vessels, and tissues. The

materia medica of the Hindus embraces a vast collection of drugs

belonging to the mineral, vegetable, and animal kingdom, many of

which have been adopted by the European physicians. Their pharmacy

contained ingenious processes of preparation, with elaborate

directions for the administration and classification of medicines.

Much attention was devoted to hygiene, to the regimen of the body,

and to diet.

The surgery of the

ancient Indian physicians appears to have been bold and skilful.

They conducted amputations, arresting the bleeding by pressure, a

cup-shaped bandage, and boiling oil. They practiced lithotomy;

performed operations in the abdomen and uterus; cured hernia,

fistula, piles; set broken bones and dislocations; and were

dexterous in the extraction of foreign substances from the body. A

special branch of surgery was devoted to rhinoplasty, or operations

for improving deformed ears and noses, and forming new ones. They

devoted great care to the making of surgical instruments, and to the

training of students by means of operations performed on wax spread

out on a board, or on the tissues and cells of the vegetable

kingdom, and upon dead animals. Considerable advances were also made

in veterinary science, and mongraphs exist on the diseases of horses

and elephants. "

(source: The

Indian Empire - By

Sir William Wilson Hunter p.148-150).

Ancient India possessed advanced medical knowledge. Her

doctors knew about metabolism, the circulatory system, genetics, and the nervous

system as well as the transmission of specific characteristics by heredity.

Vedic physicians understood medical ways to counteract the effects of poison

gas, performed Caesarean sections and brain operations, and used anesthetics.

Sushruta (5th

century BC) listed the diagnosis of 1,120 diseases. He described 121 surgical

instruments and was the first to experiment in plastic surgery.

(source:

We

Are Not The First – By Andrew Tomas

- A Bantam Book 1971 New York p. 15 -

49).

The most remarkable part of Charaka's

work is his classification of remedies drawn from vegetable, mineral and animal

sources. Over two thousand vegetable preparations, derived from the roots, bark,

flowers, fruits, seeds or sap of plants and trees, are described vy Charaka, who

also gives the correct time of year for gathering these materials and the method

of preparing and administering them. Charaka sounds

surprisingly modern. He devotes a good deal of attention to children's diseases,

and discusses proper feeding and hours of sleep. He stresses the care of the

teeth and the necessity of cleaning them. The universal custom among

Hindus of using a medicinal stick to clean the teeth and of rinsing the mouth

thoroughly after every meal is so firmly established that it must go back to

very ancient times. Diagnosis in Charaka's time was primarily based on careful

study of the pulse, and that Charaka had a good idea of blood circulation is

apparent from this passage in his treatise: "From that great center (the

heart) emanate the vessels carrying blood into all part of the body - the

element which nourishes the life of all animals and without which it would be

extinct."

Charaka's treatise was based on the teaching of Atreya,

whose date has been assigned to the sixth century B.C. Previous to Atreya,

Ayurveda, "the science of life" was one of the recognized Vedic

studies. High ethical standards which should be maintained by medical profession

were also stressed by Charaka. He says: "Not for money nor for any earthly

objects should one treat his patients. In this the physician's work excels all

vocations. Those who sell treatment as a merchandise neglect the true measure of

gold in search of mere dust."

(source: The

Pageant of India's History - By Gertrude Emerson Sen p. 66 - 67).

Horace Hayman

Wilson (1786-1860) Eminent

Orientalist, observed:

"That in medicine, or the

astronomy and metaphysics, the Hindus have kept pace with the most

enlightened nations of the world: and that they attained as thorough

a proficiency in medicine and surgery as any people whose

acquisitions are recorded." He says further: "It would

easily be supposed that their patient attention and national

shrewdness would render the Hindus excellent observers."

(source: Eminent

Orientalists: Indian European American - Asian

Educational Services. p. 77).

The great picture of Indian medicine is one of rapid

development in the Vedic and Buddhist period, followed by centuries of slow and

cautious improvement. In the time of Alexander, says

Garrison, "Hindu

physicians and surgeons enjoyed a well-deserved reputation for superior

knowledge and skill," and even Aristotle is believed by some students to

have been indebted to them. So too with the Persians and Arabs. The great picture of Indian medicine is one of rapid

development in the Vedic and Buddhist period, followed by centuries of slow and

cautious improvement. In the time of Alexander, says

Garrison, "Hindu

physicians and surgeons enjoyed a well-deserved reputation for superior

knowledge and skill," and even Aristotle is believed by some students to

have been indebted to them. So too with the Persians and Arabs.

We

find Persians and Arabs translating into their languages, in the eighth century

A.D., the thousand-year-old compendia of Sushrata and Charaka. The great Caliph Haroun-al-Rashid accepted the

preeminence of Indian medicine and scholarship, and imported Indian physicians

to organize hospitals and medical schools in Baghdad.

Lord Amphill concludes that medieval and modern Europe owes its system of

medicine directly to the Arabs, and through them to India.

(source:

The Story of civilizations:

Our Oriental Heritage - By

Will Durant ISBN:

1567310125 1937 p.531).

Dorothea Chaplin

mentions in her book,

Matter,

myth and Spirit or Keltic and Hindu Links

(pp 168-9), "Long before the year 460 B.C., in which Hippocrates, the

father of European medicine was born, the Hindus had built an extensive

pharmacopoeia and had elaborate treatises on a variety of medical and surgical

subjects....The Hindus' wonderful knowledge on a variety of medicine has for

some considerable time led them away from surgical methods as working

destruction on the nervous system, which their scientific medical system is able

to obliviate, producing a cure even without preliminary crisis."

(source: Proof

of Vedic Culture's Global Existence - By Stephen Knapp.

World Relief Network ISBN: 0961741066

p 31).

The practice of

medicine, like all other sciences, was regulated by a code of

social ethics. A physician (vaidya) was to be devoted to the

service of the sick. Charaka's advice to his students contained

the gist of the professional ethics:

"If you want

success in your practice, wealth and fame, and heaven after your

death, you must pray every day on rising and going to bed for the

welfare of all beings and you must strive with all your soul for

the health of the sick. You must not betray your patients, even at

the cost of your own life. You must not get drunk, or commit evil,

or have evil companions. You must be pleasant, of speech and

thoughtful, always striving to improve your knowledge."

Free hospitals were

maintained by the kings and merchants. Nursing and attending the

sick was considered to be one of the highest service to

dharma.

(source: Ancient

Indian History and Culture - By Chidambara Kulkarni

p. 273).

Ancient Hospitals

The Hindus were the first nation

to establish hospitals, and for centuries they were the only people in the world

who maintained them. The Chinese traveler, Fa-hien,

speaking of a hospital he visited in Pataliputra says: "Hither come all

poor and helpless patients suffering from all kinds of infirmities. They are

well taken care of, and a doctor attends them; food and medicine being supplied

according to their wants. Thus they are made quite comfortable, and when they

are well, they may go away."

"The earliest hospital in

Europe," says historian Vincent A. Smith, "is said to have been opened

in the tenth century."

(source: Early

History of India - By Vincent Smith

p. 259).

***

Smallpox inoculation started

in India before the West

Smallpox inoculation is an ancient

Indian tradition and was practiced in India before the West.

In ancient times in India smallpox

was prevented through the tikah (inoculation). Kurt

Pollak (1968) writes, "preventive inoculation

against the smallpox, which was practiced in China from the 11th

century, apparently came from India". This inoculation

process was generally practiced in large part of Northern and

Southern India, but around 1803-04 the British government banned

this process. It's banning, undoubtedly, was done in the name of

'humanity', and justified by the Superintendent General of Vaccine

(manufactured by Dr. E. Jenner from the cow for use in the

inoculation against smallpox).

Dharmapal

has quoted British sources to prove that inoculation in

India was practiced before the British did. In the seventeenth

century, smallpox inoculation (tikah) was practiced in

India. A particular sect of Brahmins employed a sharp iron needle

to carry out these practices. In 1731, Coult was in Bengal and he

observed it and wrote (Operation of inoculation of the smallpox

as performed in Bengall from Re. Coult to Dr.

Oliver Coult in 'An account of the diseases of Bengall'

Calcutta, dated February 10, 1731):

"The operation of inoculation

called by the natives tikah

has been known in the kingdom of Bengall as near as I can learn,

about 150 years and according to the Bhamanian records was first

performed by one Dununtary, a physician of Champanagar, a small

town by the side of the Ganges about half way to Cossimbazar whose

memory in now holden in great esteem as being through the another

of this operation, which secret, say they, he had immediately of

God in a dream.'

English physician Jenner is

credited with discovering vaccination on a scientific basis with

his studies on small pox in 1796. A group

of Fellows of the Royal Society had earlier studied the method of

inoculating people in India and submitted its report in the 1760s.

Dr J. Z. Holwell, one of the members who was in the Bengal Province

for more than ten years to study the Indian vaccination method,

lectured at the London Royal College of Physicians in 1767

"that nearly the same salutary method, now so happily pursued

in England,... has the sanction of

remotest antiquity (in India), illustrating the

propriety of present practice".

Dr. J. Z.

Holwell writes the most detailed account for the

college of Physicians in London in 1767 (An account of the

manner of inoculating for the smallpox in the East Indies, by

J. Z. Holwell, F.R.S. addressed to the President and Members of

the College of Physicians in London). He wrote: Dr. J. Z.

Holwell writes the most detailed account for the

college of Physicians in London in 1767 (An account of the

manner of inoculating for the smallpox in the East Indies, by

J. Z. Holwell, F.R.S. addressed to the President and Members of

the College of Physicians in London). He wrote:

"Inoculation is

performed in Indostan by a particular tribe of Bramins, who are

delegated annually for this service from the different Colleges of

Bindoobund, Eleabas, Benares, & c. over all the distant

provinces: dividing themselves into small parties, of three or

four each, they plan their traveling circuits in such wise as to

arrive at the places of the operation consists only in abstaining

for a month from fish, milk, and ghee (a kind of butter made

generally of buffalo's milk). When the Bramins begin to inoculate,

they pass from house to house and operate at the door, refusing to

inoculate any who have not, on a strict scrutiny, duly observed

the preparatory course enjoined them. It is no uncommon thing for

them to ask the parents how many pocks they choose their children

should have."

(source: An

account of the manner of inoculating for the smallpox in the East

Indies

- by J. Z. Holwell M.D., F.R.S.).

On the efficacy of this practice

Holwell has the following to say:

"When the before recited

treatment of the inoculated is strictly followed, it is next to a

miracle to hear, that one in a million fails of receiving the

infection, or of one that miscarries under it.. Since, therefore,

this practice of the East has been followed without variation, and

with uniform success from the remotest unknown times, it is but

justice to conclude, it must have been originally founded on the

basis of rational principle and experiment."

Holwell's detailed account, not

only describes inoculation, but also shows that the Indians knew

that microbes caused such diseases.

(source: Indian

Science And Technology in the Eighteenth Century; some

contemporary European accounts - By

Dharampal 1971. An Account of the manner of

inoculating for the Smallpox in the East Indies. Mapusa, Goa:

Other India Press. Chapter VIII p. 142 -164. The

Healers, the Doctor, then and now - By Pollack,

Kurt 1968.English Edition. p. 37-8.).

Also refer to Indian

Institute of Science - Prevention

of Small Pox in ancient India).

The Sactya Grantham

- ancient Brahman medical text ~ 3,500 years old describing brain surgery and

anaesthetics, contains the following passages giving instructions on small

pox vaccination:

“Take on the tip of a knife the contents of the

inflammation, inject it into the arm of the man, mixing it with his blood. A

fever will follow but the malady will pass very easily and will create no

complications.” Edward Jenner (1749-1823) is credited with the discovery

of vaccination but it appears that ancient India has prior claim!"

(source:

We

Are Not The First – By Andrew Tomas

- A Bantam Book 1971 New York p. 15 -

49).

and

http://www.habtheory.com/1/habrefs.php).

The Brahmins had a theory of their

operations. They believed the atmosphere abounded with

imperceptible animalculae (refined to bacteria within a larger

context today). They distinguished tow types of these: those that

are harmful and those not so. The Brahmins therefore

believed that their treatment in inoculating the person expelled

the immediate cause of the disease. How effective was the

inoculation? According to Dr. J. Z.

Holwell, FRS, who had addressed the College of

Physicians in London:

“When the before recited treatment of the inoculation is

strictly followed, it is next to a miracle to hear, that one in a

million fails to receiving the infection, or of one that

miscarries under it.”

A later estimate by the Superintendent General of Vaccine in

1804 noted that fatalities among the inoculated counted one in 200

among the Indian population and one in 60 to 70 among the

Europeans. There is an explanation for this divergence. Most

of the Europeans objected to the inoculation on theological

grounds.

Small pox has a long

history in India; it is discussed in the Hindu scriptures and even

has a goddess (Sitala, literally “the cool

one")

devoted exclusively to

its cause. It seems therefore almost natural to expect an Indian

medical response to the disease. The inoculation treatment against

it was carried out by a particular caste of Brahmins from the

different medical colleges in the area. These Brahmins circulated

in the villages in groups of three or four to perform their task. Small pox has a long

history in India; it is discussed in the Hindu scriptures and even

has a goddess (Sitala, literally “the cool

one")

devoted exclusively to

its cause. It seems therefore almost natural to expect an Indian

medical response to the disease. The inoculation treatment against

it was carried out by a particular caste of Brahmins from the

different medical colleges in the area. These Brahmins circulated

in the villages in groups of three or four to perform their task.

The person to be inoculated was obliged to follow a certain

dietary regime; he had particularly to abstain from fish, milk, and ghee, which,

it was held, aggravated the fever that resulted after the treatment. The method

the Brahmins followed is similar to the one followed in our own time in certain

aspects. They punctured the space between the elbow and the wrist with a sharp

instrument and then proceeded to introduce into the abrasion “various

matter” prepared from inoculated pistules from the preceding year. The purpose

was to induce the disease itself, albeit in a mild form; after it left the body,

the person was rendered immune to small-pox for life.

The Brahmins had a theory of their operations. They believed

the atmosphere abounded with imperceptible animalculae. They distinguished two

types of these: those harmful and those not so. The universality of this

practices ceased to obtain with the arrival of the British. Like many

specialists in India, including teachers, the Brahmin doctors had been

maintained through public revenues. With British rule, this fiscal system was

disrupted and the inoculators left to fend for themselves.

Two

of the more important medical arts of India – plastic surgery

and inoculations against small pox. Both were indigenously

evolved and the accounts we have, come from Westerners

sent out to study them. One

of these curious facts was the inoculation against small pox

disease, practiced in both north and south India till it

was banned or disrupted by the English authorities in 1802-3.

The ban was pronounced on “humanitarian” grounds by the

Superintendent General of Vaccine.

(source: Homo

Faber: Technology and Culture in India, China and the West 1500-1972 - By

Claude Alvares p. 65-67 and

Decolonizing

History: Technology and Culture in India, China and the West

1492 to the Present Day - By Claude Alvares

p.66-67).

European colonists from the

sixteenth century onwards, gained knowledge of plants, diseases

and surgical techniques that were unknown in the West. One such

example is rauwolfia serpentia, a plant used in traditional Indian

medicine. The active ingredient is today used to treat

hypertension and anxiety in the West.

Sir Mountstuart

Elphinstone has written:

"Their use of these medicines seems to have been very bold. They

were the first nation who employed minerals internally, and they not

only gave mercury in that manner but arsenic and arsenious acid, which

were remedies in intermittents. They have long used cinnabar for

fumigations, by which they produced a speedy and safe salivation. They

have long practiced inoculation."

"They cut for the stone, couched

for the cataract, and extracted the fetus from the womb, and in their

early works enumerate not less than 127 sorts of surgical

instruments!" "Their acquaintance with medicines seems to

have been very extensive. We are not surprised at their knowledge of

simples, in which they gave early lessons to Europe, and more recently

taught us the benefit of smoking dhatura in asthma and the use of

cowitch against worms."

(source: History

of India - Mountstuart Elphinstone London: John Murray Date of

Publication: 1849 p. 145).

The Englishman

(a Calcutta Daily), in a lead story in 1880, said: "No one can

read the rules contained in great Sanskrit medical works without

coming the conclusion that in point of knowledge, the ancient Hindus

were in this respect very far in advance not only to the Greek and

Romans but also to Medieval Europe."

(source: Sanskrit

Civilization - By G. R. Josyer p. 28).

***

Ayurveda or the Veda of Longevity

Ayurveda is a

3,000- to 5,000-year-old holistic healthcare system, which looks

at the individual, addresses diet, lifestyle and spirit, and strives

for balance in each person. It

focuses on prevention,

and sees, many illnesses not as a collection of symptoms but as

imbalances within the body, mind or spirit that, once balance is

restored, eats disease at its root.

"The science

of Medicine was cultivated early in India and modern researches have

disclosed the fact that the Materia Medica of the Greeks, even of

Hippocrates the "Father of Medicine," is based on the

older Materia Medica of the Hindus....

Charaka's work is divided into eight books, describing various

diseases and their treatment; and Susruta's work has six parts, and

specially treats of surgery and operations which are considered

difficult even in modern times. Various chemical processes were

known to the Hindus. Oxides, sulphates, and suphurets of various

metals were prepared, and metallic substances were administered

internally in India long before the Arabs borrowed the practice from

them, and introduced it in Europe in the Middle Ages."

(source: The

Civilization of India - By Romesh C. Dutt

p. 64).

A

tree resin used in Indian medicine for

2,000 years as a folk remedy for a variety of ailments

works to lower cholesterol in lab animals, and in a new way that

might lead to the development of improved drugs for people, U.S.

researchers report.

The

tree is known in India as guggul,

or the myrrh shrub. It’s been used there since at least 600 BC to

battle obesity and arthritis, among other ailments.

(source:

Ancient

remedy could lead to alternative to today’s drugs

- msnbc.com).

"Indian

medicine's influence on Portugal was fairly wide. You had echoes of Indian or

Ayurvedic practices that come into Portuguese usage. Tamarind,

for example, is a plant widely used in Ayurveda. It is applied in Portuguese

hospitals. It is used as a cooling agent, in combination with other medicinal

plants to help the absorption of those plants and it is used in a poultice,

placed on the skin.

(source:

West

has always benefited from Indian medicine).

"Hindu literature on anatomy and

physiology as well as eugenics and embryology has been voluminous.

The Hindus knew the exact osteology of the human body 2,000 years

before Vesalius (c. 1545) and had some rough ideas of the

circulation of blood long before Harvey (1628). the internal

administration of mercury, iron and other powerful metallic drugs

were practized by the Hindu physicians at least 1,000 years before

Paracelsus (1540). And they have written extensive treatises on

these subjects."

(source: Creative

India - By Benoy Kumar Sarkar published Motilal Banarsi

Dass, Lahore 1937. p. 5).

Ayurveda is a traditional

healing system of India, with origins firmly rooted in the culture of the Indian

subcontinent. Some 5000 years ago, the great rishis, or

seers of ancient India, observed the fundamentals of life and organized them

into a system. Ayurveda was their gift to us, an oral tradition

passed down from generation to generation. Ayurvedic

teachings were recorded as sutras, succinct poetical verses in Sanskrit,

containing the essence of a topic and acting as aides-memoire for the students.

Sanskrit, the ancient language of India, reflects the philosophy behind Ayurveda

and the depth within it. Sanskrit has a wealth of words for aspects within and

beyond consciousness.

A

few treatises on Ayurveda date from around 1000 B.C. The best known is Charaka

Samhita, which concentrates on internal medicine. Many of today’s Ayurvedic

physicians use Astanga Hrdayam, a more concise compilation written over 1000

years ago from the earlier texts.

(source: The

Book of Ayurveda: A Holistic Approach to Health and Longevity - By Judith H.

Morrison p. 15 -20).

US

medical schools to teach Ayurveda

American

medical schools will teach students the goodness of Ayurveda with visiting

Indian specialists offering a 12-hour crash course programme on the medical

system based on herbs.

Schools in the

United States

are offering the course taught by Dr Palep under the aegis of Complementary

Alternative Medicine and include topics like Ayurveda philosophy, anatomy,

physiology, pathology, pharmacology, clinical exam and treatments. It also

teaches Yoga, meditation and panchkarma therapy

(process of detoxification and rejuvenation).

(source:

US

medical schools to teach Ayurveda

- sify.com).

Veterinary science in Ancient India

Since animals were regarded as a part of

the same cosmos as humans, it is not surprising that animal life was keenly

protected and veterinary medicine was a distinct branch of science with its own

hospitals and scholars. Numerous texts, especially of the postclassical period, Visnudharmottara

Mahapurana for example, mention veterinary

medicine. Megasthenes refers to the kind of treatment which was later to be

incorporated in Palakapyamuni's Hastya yur Veda

and similar treatises. Salihotra

was the most eminent authority on horse breeding and hippiatry. Juadudatta

gives a detailed account of the medical

treatment of cows in his Asva-Vaidyaka. Since animals were regarded as a part of

the same cosmos as humans, it is not surprising that animal life was keenly

protected and veterinary medicine was a distinct branch of science with its own

hospitals and scholars. Numerous texts, especially of the postclassical period, Visnudharmottara

Mahapurana for example, mention veterinary

medicine. Megasthenes refers to the kind of treatment which was later to be

incorporated in Palakapyamuni's Hastya yur Veda

and similar treatises. Salihotra

was the most eminent authority on horse breeding and hippiatry. Juadudatta

gives a detailed account of the medical

treatment of cows in his Asva-Vaidyaka.

(source: India and World Civilization

- By D. P. Singhal Pan Macmillan Limited. 1993.

p.187-188).

According to Stanley

Wolpert, " Veterinary science had

developed into an Indian medical specialty by that early era, and India's

monarchs seem to have supported special hospitals for their horses as well as

their elephants. Hindu faith in the sacrosanctity of animals as well as human

souls, and belief in the partial divinity of cows and elephants helps explain

perhaps what seems to be far better care lavished on such animals... A uniquely

specialized branch of Indian medicine was called Hastyaurveda

("The Science of Prolonging Elephant Life").

(source: An

Introduction to India - By Stanley Wolpert

p. 193-194).

Top

of Page

Astronomy

The science of astronomy flourishes only amongst

a civilized people. Hence, considerable advancement in it is itself proof of the

high civilization of a nation. Hindu astronomy has received the homage of

numerous European scholars.

Sir William Hunter (1840-1900)

says

"The Astronomy of the Hindus has formed the subject of excessive

admiration."

"Proof of very extraordinary

proficiency," says

Lord Elphinstone, "in

their astronomical writings are found."

(source: Hindu Superiority

- By Har Bilas

Sarda p. 332 - 348).

William

Robertson wrote: "It is

highly probable that the knowledge of the twelve signs of zodiacs

was derived from India."

(source: An

Historical Disquisition Concerning the Knowledge which the Ancients

had of India - By

William

Robertson p. 280).

India has left a universal legacy

determining for instance the dates of solstices, as noted by 18th century French

astronomer Jean-Claude Bailly

(1736–93) 18th century French astronomer and politician. His works on

astronomy and on the history of science (notably the Essai sur la théorie

des satellites de Jupiter and History

of Astronomy) were distinguished both for scientific interest

and literary elegance and earned him membership in the French Academy, the

Academy of Sciences, and the Academy of Inscriptions. Bailly, who was

guillotined during the French Revolution, maintained that the Brahmins of India

had been tutors of the Greeks and, through them, of Europe.

Jean-Claude

Bailly

said: Jean-Claude

Bailly

said:

" The motion of the

stars calculated by the Hindus before some 4500 years vary not even

a single minute from the tables of Cassine and Meyer (used in the

19-th century). The Indian tables give the same annual variation of

the moon as the discovered by Tycho Brahe - a variation unknown to

the school of Alexandria and also to the Arabs who followed the

calculations of the school... "The Hindu systems

of astronomy are by far the oldest and that from which the Egyptians, Greek,

Romans and - even the Jews

derived from the Hindus their knowledge."

(source: The Politics of

History - By N. S. Rajaram Voice of India ISBN 81-85990-28-X. 1995 p.

47).

The paper of John

Playfair (1748-1819) (FRS and Professor of Mathematics at the

University of Edinburgh) is a detailed review (published in 1790)

of the book 'Traite de ';astronomie Indienne et Orientale,' by J.

S. Bailly (Paris 1787), the famous French historian of astronomy.

Taken as if by surprise by Bailly's rather positive evaluation of

the origin, antiquity and achievements of Indian astronomy,

Playfair states that: "I entered on the study of that work,

not without a portion of skepticism....The result was, an entire

conviction of the accuracy of the one, and of the solidity of the

other.' Both Bailly's book and Playfair's article examine in

detail some of the astronomical tables (based on Indian astronomy)

that the French had procured from Siam (Thailand), Playfair's main

conclusions are the following:

1. The observations on which the

astronomy of India is founded, were made more than three thousand

years before the Christian era; and in particular, the places of

the sun and the moon, at the beginning of the Kali-yoga/Calyougham

(i.e., 17/18 February 3102 B.C.), were determined by actual

observation.

2. Though the astronomy which is

now in the hands of the Brahmins, is so ancient in its origin, yet

it contains many rules and tables that are of later

construction.

3. The basis of the four systems of

astronomical tables which we have examined, is evidently the same.

4. The construction of these tables

implies a great knowledge of geometry, arithmetic, and even of the

theoretical part of astronomy.

Playfair argues that 'communication

is more likely to have gone from India to Greece, than in the

opposite direction."

(source: India

Through The Ages: History, Art Culture and Religion - By G. Kuppuram

p.671-672).

Hindu astronomy received considerable

homage from European scholars. Sir William

Hunter (1840-1900) says: "The astronomy of the Hindus has formed

the subject of excessive admiration." "In some points the

Brahmins made advances beyond Greek astronomy. Their fame spread

throughout the West, and found entrance into the Chronicon Paschale

(commenced about 330 A.D. and revised under Heraclius 610-641).

"The Sanskrit term for the apex of a planet's orbit seems to

have passed into the Latin translations of the Arabic astronomers.

The Sanskrit uccha became the aux (genaugis) of the later

translators." "The Arabs became their (Hindus) discipline

in the 8th century, and translated Sanskrit treatises, Siddhanats,

under the name Sindhends."

Albrecht Weber

(1825-1901) says: Albrecht Weber

(1825-1901) says:

"The fame of Hindu astronomers spread to the

West, and the Andubarius (or probably, Ardubarius), whom the Chronicon Paschale

places in primeval times as the earliest Indian astronomer, is doubtless none

other than Aryabhatta, the rival of Pulisa, and who is likewise extolled by the

Arabs under the name of Arjabahar."

(source: Indian

Literature - By Albrecht Weber ISBN: 1410203344 p. 255).

Research scholars like Sylvain

Bailley (1736-1793) and Charles Francois

Dupuis (1742-1809) aver that the Hindu

Zodiac is the earliest known to man and that the first calendar was made in

India in about B.C. 12,000.

(Refer to Bailley's Histoire

de Astonomie Ancienne p. 483 as well as the Proceedings of the

Society of Biblical Archaeology - December 1901 part I).

The Hon. Emmeline M.

Plunket (1835- ) in the great work Ancient

Calendars and Constellations p. 192 - says that there were very

advanced Hindu Astronomers in B.C. 6,000.

(source: Hinduism: That

Is Sanatana Dharma - By R. S. Nathan p. 38 published by Central

Chinmaya Mission Trust. Bombay).

Horace Hyman

Wilson (1786-1860) wrote: "The science of astronomy at present

exhibits many proofs of accurate observation and deduction, highly

creditable to the science of the Hindu astronomers. The division of

the ecleptic into lunar mansions, the solar zodiac, the mean motions of the

planets, the procession of the equinox, the earth's self-support in space, the

diurnal revolution of the earth on its axis, the revolution of the moon on her

axis, her distance from the earth, the dimensions of the orbits of the planet,

the calculations of eclipses are parts of a system which could not have been

found amongst an unenlightened people."

But the originality of the Hindus is not less

striking than their proficiency. Wilson says: "The originality of Hindu

astronomy is at once established, but it is also proved by intrinsic evidence,

and although there are some remarkable coincidences between the Hindu and other

systems, their methods are their own."

(source: History

of British India

- by James Mill Volume II p,

106-107).

Mountstuart

Elphinstone wrote: "Proofs of very extraordinary

proficiency in their astronomical writings are found."

The Hindu astronomy not only

establishes the high proficiency of our ancestors in this department

of knowledge and exacts admiration and applause: it does something

more. It proves the great antiquity of the Sanskrit literature and

the high literary culture of the Hindus. "Monsieur

Bailly, the celebrated author of the History of

Astronomy, inferred from certain astronomical tables of the Hindus,

not only advanced progress of the science, but a date so ancient as

to be entirely inconsistent with the chronology of the Hebrew

scriptures. His argument was labored with the utmost diligence and

was received with unbounded applause. All concurred at the time with

the wonderful learning, wonderful civilization and wonderful

institutions of the Hindus!"

(source: History

of British India

- By James Mill Volume II. p. 97-98).

Albrecht Weber

(1825-1901) says: "Astronomy was practiced in India as early as 2780

B.C." "The fame of Hindu astronomers spread to the

West, and the Andubarius (or probably, Ardubarius), whom the

Chronicon Paschale places in primeval times as the earliest Indian

astronomer, is doubtless none other than Aryabhatta, the rival of

Pulisa, and who is likewise extolled, by the Arabs under the name of

Arjabahar."

(source: Indian

Literature - By Albrecht Weber p. 30-255).

But

some of the greatest modern astronomers have decided in favor of a

much greater antiquity. Cassini, Bailly, Gentil and Playfair

maintain "that there are Hindu observations extant which must

have been made more than three thousand years before Christ, and

which evince even then a very high degree of astronomical

science." But

some of the greatest modern astronomers have decided in favor of a

much greater antiquity. Cassini, Bailly, Gentil and Playfair

maintain "that there are Hindu observations extant which must

have been made more than three thousand years before Christ, and

which evince even then a very high degree of astronomical

science."

Count

Magnus Fredrik Ferdinand Bjornstjerna (1779-1847)

proves conclusively that Hindu astronomy was very far advanced even at the

beginning of the Kaliyug, or the iron age of the Hindus (about 5,000 years ago).

He says: "According to the astronomical calculations of the Hindus, the

present period of the world, Kaliyug, commenced 3,102 years before the birth of

Christ, on the 20th of February, at 2 hours 27 minutes and 30 seconds, the time

being thus calculated of the planets that took place, and their tables show this

conjunction. Bailly states that Jupiter and Mercury were then in the same degree

of the ecliptic, Mars at a distance of only eight, and Saturn of seven degrees;

whence it follows, that at the point of time given by the Brahmins as the

commencement of Kaliyug, the four planets above-mentioned must have been

successively concealed by the rays of the sun (first Saturn, then Mars,

afterwards Jupiter and lastly Mercury)....The calculation of the Brahmins is so

exactly confirmed by or own astronomical tables, that nothing but an actual

observation could have given so correspondent a result."

The learned Count

continues: "He (Bailly) further informs

us that Laubere, who was sent by Louis XIV as

ambassador to the King of Siam, brought home, in the year 1687, astronomical

tables of solar eclipses and that other similar tables were sent to Euorpe by

Patouillet (a missionary in the Carnatic - India), and by Gentil, which later

were obtained from the Brahmins in Tirvalore, and that they all perfectly agree

in their calcuations although received from different persons, at different

times, and from places in India remote from each other. On these tables Bailly,

makes the following observation. The motion calculated by the Brahmins during

the long space of 4,385 years (the period eclipsed between these calculations

and Bailly's), varies not a single minute from the tables of Cassini and Meyer;

and as the tables brought to Europe by Laubere in 1687, under Louis XIV, are

older than those of Cassini and Meyer, the accordance between them must be the

result of mutual and exact astronomical observations." Then again,

"Indian tables give the same annual variation of the moon as that

discovered by Tycho Brahe, a variation unknown to the school of Alexandria, and

also to the Arabs, who followed the calculation of this school."

"These facts," says the erudite Count,

"sufficiently show the great antiquity and distinguished station of

astronomical science among the Hindus of past ages." The Count then asks

"if it be true that the Hindus more than 3,000 BC., according to Bailly's

calculation, had attained so high a degree of astronomical and geometrical

learning, how many centuries earlier must the commencement of their culture have

been, since the human mind advances only step by step on the path of

science."

The length of the Hindu tropical year as deduced

from the Hindu tables is 365 days, 5 hours, 50 minutes, 35 seconds, while La

Callie's observation given 365-5-48-49. This makes the year at the time of the

Hindu observation longer than at present by 1'46". It is however, an

established fact that the year has been decreasing in duration from time

immemorial and shall continue to decrease.

(source: The

Theogony of the Hindoos with their systems of Philosophy and

Cosmogony

- By Count Bjornstjerna p. 32).

W Brennand

had said in his book Hindu

Astronomy:

"It

is certain that the ancient Hindu astronomers, many centuries before

the Christian Era, were in possession of knowledge, derived from

observations made by them of the motions of the heavenly bodies,

which they were able to use, and did actually use, in very accurate

computations of time. "

"Upon

the first point (the antiquity of that system), it may be remarked, that no one

can carefully study the information collected by various investigators and

translators of Hindu works relating to Astronomy, without coming to the

conclusion that, long before the period when Grecian learning founded the basis

of knowledge and civilization in the West, India had its own store of erudition.

Master minds, in those primitive ages, thought out the problems presented by the

ever recurring phenomena of the heavens, and gave birth to the ideas which were

afterwards formed into a settled system for the use and benefit of succeeding.

Astronomers, Mathematicians, and Scholiasts, as well as for the guidance of

votaries of religion."

It is in

the light of such consideration as these, that the investigator of the facts

relating to Hindu Astronomy, is compelled to admit the extreme antiquity of the

science. An impartial investigation of the circumstances relating to the

question whether the Grecian Astronomy was original in its nature, and was

copied by the Hindus, places it beyond doubt that the Hindu system was

essentially different from and independent of the Greek.

“No

nation in existence can afford to compare to latter [India] in many tenets of

science, with its earliest theories and cosmography, without a smile at the

expense of ancestors, but the Hindus, in this view, may, with not a little

justifiable pride, point to their science of astronomy, arithmetic, algebra,

geometry and even of trignometry, as containing within them evidence of a

traditional civilisation compared formally with that of any other nation in the

world.”

(source: Hindu

Astronomy

- By W Brennand p.

34 and 320 - 323).

Paul

G Johnson has observed in his book, God and World

Religions: Paul

G Johnson has observed in his book, God and World

Religions:

"In 600 B.C.E.

the writer of Genesis perceived Earth to be the motionless

centerpiece of creation, and above its flat surface were two great

lights – the Sun and the Moon. Fourteen

centuries before, the Hindu scripture – The

Rig Veda – had a more accurate

picture. Not only did the Sun, Moon, and Earth revolve in orbits,

but “the Earth in its orbit revolves around the Sun.” (8:2).

(source: God

and World Religions - By Paul

G Johnson p. 3).

"In India,

we see the beginning of theoretical speculation of the size and

nature of the earth. Some one thousand years before Aristotle,

the Vedic Aryans asserted

that the earth was round and circled the sun. A translation of

the Rig Veda goes: " In

the prescribed daily prayers to the Sun we find..the Sun is at

the center of the solar system. ..The student ask, "What is

the nature of the entity that holds the Earth? The teacher

answers, "Rishi Vatsa holds

the view that the Earth is held in space by the Sun."

"Two

thousand years before Pythagoras, philosophers

in northern India had understood that gravitation held the solar

system together, and that therefore the sun, the most massive

object, had to be at its center."

"Twenty-four

centuries before Isaac Newton, the Hindu Rig-Veda

asserted that gravitation held the universe together. The

Sanskrit speaking Aryans subscribed to the idea of a spherical

earth in an era when the Greeks believed in a flat one. The

Indians of the fifth century A.D. calculated the age of the

earth as 4.3 billion years; scientists in 19th century England

were convinced it was 100 million years."

(source: Lost

Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science - By Dick

Teresi p. 1 - 8 and 159 and 174 -239).

For more on Dick Teresi refer to chapters Quotes301_320,

GlimpsesVI and GlimpsesVII

).

Historian A.

L. (Arthur Llewellyn) Basham wrote: Historian A.

L. (Arthur Llewellyn) Basham wrote:

"The procession of the equinoxes

was known, and calculated with some accuracy by medieval

astronomers, as were the lengths of the year, the lunar month, and

other astronomical constants. These calculations were reliable for

most practical purposes, and in many cases more accurate than those

of the Greco-Roman world. Eclipses were forecast with accuracy and

their true cause understood."

These were achieved without the help

of a telescope. Accurate measurement was made possible by the

decimal system of numerals, invented by the Indians.

It is certain that the Vedic Indians knew something of

astronomy and that it had a high utilitarian value for them as it did for all

peoples of antiquity. The Vedic priests had to make careful calculations of

times for their rituals and sacrifices, and also had to determine the time of

sowing and harvest. Moreover, astronomical periods played an important role in

Vedic thought for they were considered to be successive parts of the ever

returning cosmic cycle.

The Rig Veda lists a number of stars and mentions twelve divisions of the sun's

yearly path (rashis) and also 360 divisions of the circle. Thus, the year of 360

days is divided into twelve months. The sun's annual course was described as a

wheel with twelve spokes, which correspond to the twelve signs of the

zodiac.

The theory of the great cycles of the universe and the

ages of the world is of older origin than either Greek or Babylonian

speculations about the "great year," the period within which all the

stars make a round number of complete revolutions. But there is remarkably close

numerical concordance in these theories. The Indian concept of the great year (mahayuga)

developed from the idea of a lunisolar period of five years, combined with the

four ages of the world (yugas) which were thought to be of unequal perfection

and duration, succeeding one another and lasting in the ration of 4:3:2:1.

The

last, the Kaliyuga,

was one-tenth of the mahayga or 432,000 years. This figure was calculated not

only from rough estimates of planetary and stellar cycles, but also from the

10,800 stanzas of the Rig Veda, consisting of 432,000 syllables. The classical

astronomers calculated the great period as one of 4,320,000 years, the basic

element of which was a number of sidereal solar years, 1,080,000 a multiple of

10,800. According to Berossus, the Babylonian great year was a period of 432,000

years, comprising 120 "saroi" of 3,600 years apiece.

The Rig Veda talks

about the annual motion of the earth. The diurnal motion is

described in the Yajur Veda. The Aiteriya Brahmana explains that

"the sun neither sets nor rises, that when the earth, owing to

the rotation on its axis is lighted up, it is called day" and

so on.

(source: Haug's Aitreya Brahmana Volume II. p. 242).

The Indian astronomer, Aryabhata

lived in during the period in which the

Surya

Siddhanta

was composed. He was born in 476 and reputedly completed his famous

work, Aryabhatiya,

at the age of twenty-three. A concise and brilliant work of astronomy and

mathematics.

The Aryabhatiya introduced certain new concepts, like Aryabhata's

new epicyclic theory,

the sphericity of the

earth, its rotation on its axis and revolution around the sun,

the

true explanation of eclipses and methods of forecasting them with accuracy, and

the correct length of the year were his outstanding contributions. The Arabs

preserved the theory of sphericity of earth, and Pierre d'Ailly employed it in

1410 in his map, which was used by Columbus.

As regards the stars

being stationary, Aryabhatta

says:

"The starry

vault is fixed. It is the earth which, moving round its axis, again

and again causes the rising and setting of planets and stars."

He starts the question: "Why do the stars seem to move? and

himself replies: "As a person in a vessel, while moving

forwards sses an immovable object moving backwards, in the same

manner do the stars, however immovable, seem to move

daily."

The Polar days and

nights of six months are also described by him. T.

E. Colebrooke says:

"Aryabhatta affirmed the diurnal revolutions of the earth on

its axis. He possessed the true theory of the causes of solar and

lunar eclipses and disregarded the imaginary dark planets of

mythologists, affirming the moon and primary planets to be

essentially dark and only illuminated by the sun."

(source: T.

E. Colebrooke's Essays, Appendix G. p. 467).

For more refer to Surya

Siddhanta.

Centuries ago

Aryabhatta told Pluto is not a planet

"Indian astrology did not include Pluto as a

planet and the latest announcement by leading global astronomers

after a marathon week-long meeting at Prague on Thursday only

endorsed the Indian mathematical astrology of Aryabhatta and

Varahamihira in the sixth century," eminent mathematical

astrologer Mangal Prasad told PTI. "Western astrology uses

Pluto as a planet while Pluto was always out of Indian astrology and

we do not use it in our calculations. This is the practice from the

days of Aryabhatta and Varahamihira," Prasad said.

"Indian astrology is mathematically concerned

with the nine planets, two of which are Rahu and Ketu that are

nothing but derivatives from the diameter of the Earth, which is a

circle having a value Pi (22/7) imbedded in the equator of

earth," he said.

"This was discovered and mathematically shown

by Aryabhatta and Varahamihira in the sixth century during the

golden period of the Guptas," said Prasad, the author of books

based on the work of the two great sixth century scientists.Indian

astrology is concerned more with astronomy and the derivations are

from the equator of the Earth, diameter of the moon, the solar year

and how the planets are viewed in the northern lattitudinal region

during January and February, soon after the sun has crossed the

Tropic of Capricon and moved towards the northern part of the

hemisphere.

(source: Pluto

demotion vindicates Aryabhatta

- ibnlive.com).

As regards to the

size of the earth, it is said: "The circumference of the earth

is 4,967 yojanas and its diameter is 1,581 1/24 yojanas. A yojanas

is equal to five English miles, the circumference of the earth would

therefore be 24, 835 miles, and its diameter 7, 905 5/24 miles.

The

Yajur Veda

says that the earth is kept in space owing to the superior

attraction of the sun. The theory of gravity is thus described in

the Siddhanta

Shiromani centuries

before Newton was born: The

Yajur Veda

says that the earth is kept in space owing to the superior

attraction of the sun. The theory of gravity is thus described in

the Siddhanta

Shiromani centuries

before Newton was born:

"The earth,

owing to its force of gravity, draws all things towards itself, and

so they seem to fall towards the earth." etc..

As regards to the

solar and lunar eclipses it is said: "When the earth in its

rotation come between the sun and the moon, and the shadow of the

earth falls on the moon, the phenomenon is called lunar eclipse, and

when the moon comes between the sun and earth the sun seems as if it

was being cut off - this is solar eclipse.

The following is

taken from Varahamihira's

observations on the moon:

"One half of the

moon, whose orbit lies between the sun and the earth, is always

bright by the sun's rays; the other half is dark by its own shadows,

like the two sides of a pot standing in the sunshine."

About the eclipses,

he says: "The true explanation of the phenomenon is this: in an

eclipse of the moon, he enters into the earth's shadow; in a solar

eclipse the same thing happens to the sun. Hence the commencement of

a lunar eclipse does not take place from the west side, nor that of

the solar eclipse from the east."

(source: Brihat

Samhita

Chapter V v. 8).

Brahmagupta who was born in 598 and worked in Ujjain,

foreshadowed Newton by declaring that " all things fall to the earth by a

law of nature, for it is the nature of the earth to attract and keep

things".

But the law of gravitational

itself was not anticipated.

Recognition of the superiority of the Vedic mathematics

was also recorded as long as 662 A.D. by Severus

Sebokht, the Bishop of Qinnesrin in North Syria.

As

reported in Indian Studies in Honor of Charles

Rockwell (Harvard University Press. Cambridge,

MA. Edited by W. E. Clark, 1929), Sebokht

wrote that the Indian discoveries in astronomy

were more ingenious than those of the Greeks or Babylonians, and their numerical

(decimal) system surpasses description.

"I

will omit all discussion of the science of the Hindus [Indians], a people not

the same as Syrians, their subtle discoveries in the science of astronomy,

discoveries more ingenious than those of the Greeks and the Babylonians; their

valuable method of calculation [the decimal system]; their computing that

surpasses description. I wish only to say that this computation is done by means

of nine signs. If those who believe because they speak Greek, that they have

reached the limits of science should know these things, they would be convinced

that there are also others who know something."

(source: Proof

of Vedic Culture's Global Existence - By Stephen Knapp.

World Relief Network ISBN: 0961741066

p 22)

The celebrated European

astronomer, John

Playfair

(1748-1819) says: "The Brahmin obtains his result with wonderful certainty

and expedition in astronomy."

(source: Playfair on the

astronomy of the Hindus. Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great

Britain and Ireland. Volume II. p. 138-139).

Professor Sir

M. Williams wrote:

"It is their science of astronomy by which the (Hindus) heap billions upon

millions, trillions upon billions of years, and reckoning up ages upon ages,

eons upon eons, with even more audacity than modern geologists and astronomers.

In short, an astronomical Hindu ventures on arithmetical conceptions quite

beyond the mental dimensions of anyone who feels himself incompetent to attempt

a task of measuring infinity."

Mrs. Charlotte Manning exclaimed: "The

Hindus had the widest range of mind of which man is capable."

***

Bramin's

Observatory At Benares - By Sir Robert Barker

Benares in the East Indies,

one of the principal seminiaries of the Bramins or priests of the original

Gentoos of Hindostan, continues still to be the place of resort of that sect of

people; and there are many publick charities, hospitals, and pagodas, where some

thousands of them now reside. Having frequently heard

that the ancient Brahmins had a knowledge of astronomy, and being

confirmed in this by their information of an approaching eclipse both of the Sun

and Moon, I made inquiry, when at that place in the year 1772, among the

principal Bramins, to endeavor to get some information relative to the manner in

which they were acquainted of an approaching eclipse.

(source: Indian Science and

Technology in the 18th Century - By Dharampal).

***

Sun the

center of the Solar System

Dick

Teresi has observed that:

"The Vedas recognized the

sun as the source of light and warmth, the source of life, and center of

creation, and the center of the spheres. This perception may have planted a

seed, leading Indian thinkers to entertain the idea of heliocentricity long

before some Greeks thought of it. An ancient Sanskrit couplet

also contemplates the idea of multiple suns:

"Sarva

Dishanaam, Suryaham Suryaha, Surya."

Roughly translated this means,

"There are suns in all directions, the night sky being full of them,"

suggesting that early sky watchers may have realized that the visible stars are

similar in kind to the sun. A hymn of the Rig Veda,

the Taittriya Brahmana, extols,

nakshatravidya (nakshatra means stars; vidya, knowledge)."

"Two

thousand years before Pythagoras, philosophers in northern India had understood

that gravitation held the solar system together, and that therefore the sun, the

most massive object, had to be at its center. "

(source: Lost

Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science - By Dick Teresi

p. 1 and 130). For more refer to Surya

Siddhanta.

Ancient

Indians knew Atlantic Ocean

Buddhist Jataka stories

wrote about large Indian ships carrying seven hundred people. In the Artha

Sastra, Kautilya wrote about the Board of Shipping and the Commissioner of Port

who supervised sea traffic. The Harivamsa informs that the first geographical

survey of the world was performed during the period of Vaivasvata. The towns,

villages and demarcation of agricultural land of that time were charted on maps.

Brahmanda Purana provides the best and most

detailed description of world map drawn on a flat surface using an accurate

scale. Padma Purana says that world maps were prepared and maintained in book

form and kept with care and safety in

chests.

Surya

Siddhanta speaks about construction of wooden

globe of earth and marking of horizontal circles, equatorial circles

and further divisions. Some Puranas say that the map making had great practical

value for the administrative, navigational and military purposes. Hence the

method of making them would not be explained in general texts accessible to the

public and were ever kept secret. Surya Siddhanta says that the art of